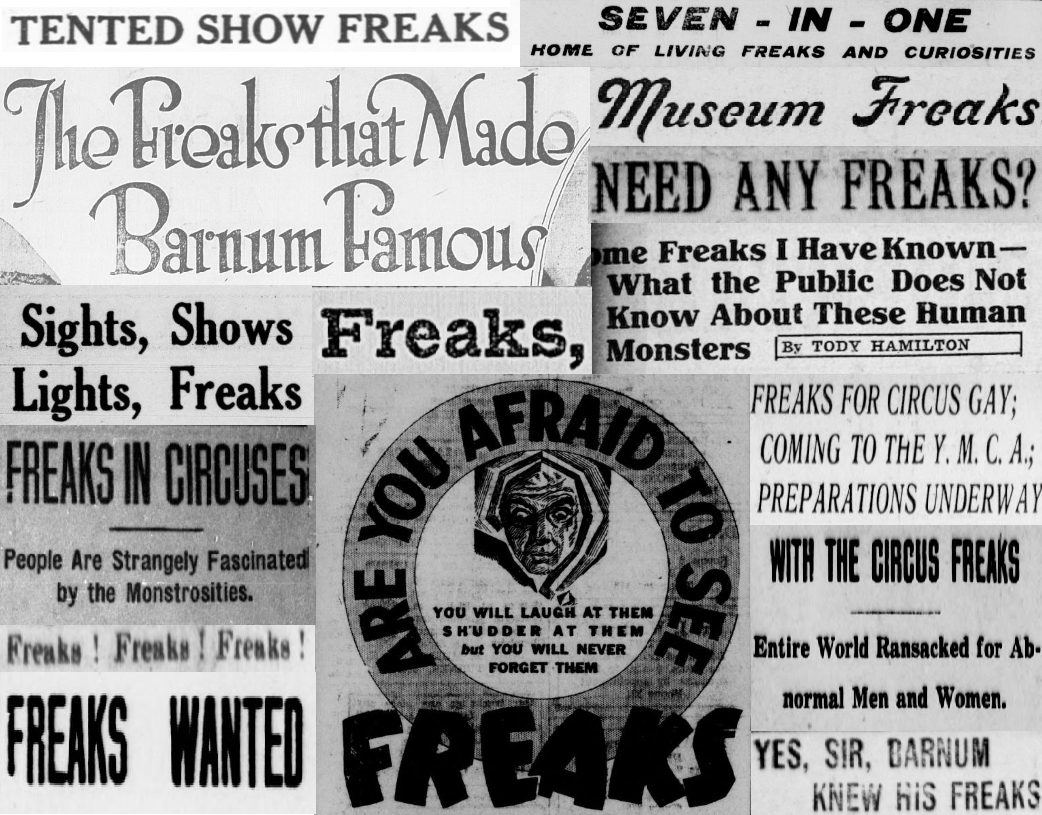

“Freakshows”—that being, the displaying of primarily people with disabilities for entertainment—emerged in the early 19th century as an aspect of the traveling circus and dime museum scenes, with names like P.T. Barnum at the forefront of the exploitation.

The advancement of photography made it so you didn’t even have to leave town to see these unusual sights. A photographer could capture their subject almost immediately and just as easily produce copies to sell for a small fee. Cartes-de-visite were often sold as souvenirs and mementos. Subjects could range from a posed comedic tableau, all the way to pictures of celebrities. And these circus performers were certainly the celebrities of their time.

In the world of photographing human oddities, none were more famous than Charles Eisenmann and Obermüller and Kern, with both studios located in New York.

Charles Eisenmann was a close associate of P.T. Barnum, and photographed many of his most famous acts. If you’ve looked even briefly into the history of the circus, you’ve undoubtedly seen his photos of Fedor “Jo Jo the Dog-Faced Boy” Jeftichew or “the original Siamese Twins” Chang and Eng Bunker. He photographed both authentic performers and fakes (gaffs) alike.

Little can be found online about Obermüller and Kern (alternatively spelled Obermiller and Kern as seen on the card as shown below, as well as Obermuller and Kern), but the sheer amount of circus performers they photographed cannot be overstated. I was able to find dozens of examples with one search.

Our museum collections house two of these cartes-de-visite. How these cards from New York ended up in our archives is no great mystery. They were (and still are, to an extent, as they can be found at secondhand shops around the country for a pretty price) a popular novelty to be sent to friends and displayed as a unique oddity.

One card displays a couple with a form of dwarfism, and the other of a pair of conjoined twins. The latter was helpfully labeled as Giovanni and Giacomo Tocci, but the former, with its envelope labeled simply and demeaningly as “midgets,” required more intense research.

My purpose in this article is not to gawk. Certainly enough have done that over the hundred-and-some odd years since the photos in this article have been taken. Instead, it is to shine a light on the subjects’ lives beyond the spectacle, because they were just as human as the rest of us, and deserving of the same amount of respect as anyone else who shows up in our newsletter.

My search was aided by the Syracuse University Library’s digital collections, home of the Ronald G. Becker Collections of Charles Eisenmann Photographs. The back of the card in our collection provides the name “Major Littlefinger,” but a stage name tells me nothing about this couple. After literal hours of clicking between reference tabs, I could finally confirm that we were looking at a photo of Robert Huzza and his wife.

Major Littlefinger’s Big Life

Robert Henry Huzza, who performed under the name Major Littlefinger, was born on February 2, 1864 in Boston. He began performing in circuses from a young age, reaching the height of only 3’6″ due to his achondroplasia. Over the course of his life he would lend his talents to several traveling circuses and dime museums, often performing in uniform as “the little cop.”

He married the recently-divorced performer Mollie Shade nee McDougal, known as the “The Lilliputian Queen,” on June 5, 1881 at the center of a circus ring in her hometown of Osceola, Iowa. Mollie would unfortunately pass away a year later on June 24, 1882 giving birth to their daughter Dollie, who would also pass away from unspecified causes within Robert’s lifetime in 1901 at the age of 18.

Ida Hosmer, Robert’s second wife who we can see in the photo below, was born in Hartford, Connecticut on August 7, 1851. She met Robert at her church shortly after the death of his first wife, where she recited poetry to him. He proposed a week later. She accepted the proposal after further wooing in the form of letters.

The two were married two weeks later on March 7, 1883 on stage at George Bunnell’s Dime Museum in New York, where Robert was currently employed, with the ceremony performed by Reverend Hugh O. Pentecost (Ida’s hometown pastor) and attended by their colleagues from the museum and the public alike.

Robert was a freemason at the Zeredetha Lodge in Brooklyn, having reached the highly respected degree of master in December 1891.

Ida passed away from pneumonia in November of 1910 in New Jersey at the age of 59. The couple had no children.

Robert would go on to marry Anna K. Buster and the two would later have a son, Buster Huzza, in Washington state in 1913. The three of them were exhibited around the state as the smallest living family. The couple would eventually retire from the circus scene and move to Florida, where Buster was enrolled in school as well as the local scout troop.

Robert passed away on December 14, 1929, in Jacksonville, Florida at the age of 65. At the time of his death, his occupation was listed as a peddler. Anna would outlive him by 8 years, passing away in August of 1937 in Augusta, Maine.

I found myself getting attached to this family the more I researched them, and could hardly stop once I had started. So, despite the passing of the main subject of this section, I kept going with research into the life of his son, Buster.

Buster would continue the family tradition of appearing in renowned circuses such as the Ringling Brothers for a time and was known for his skill with a whip. Reportedly, he could cut paper into thin strips and snap a cigarette from someone’s mouth with just his 10’ whip.

Beyond his circus career, Buster’s other jobs included traffic cop and mascot of a fire brigade. He, too, was a freemason like his father, and was part of Neguemkeag Lodge in Vassalboro, Maine. Along with his masonic work, he was also an active part of the local shriners and performed as a clown at various events and children’s hospital visits.

I lost track of Buster after the 1953 article below. Reprints of his life story written by a childhood friend appeared until at least the 1960s, but I could find no further updates on his life: no wedding announcements, no birth announcements, no obituaries. From what we do have, though, it seems Buster lived a long, rich life and was respected by his peers.

The Case of the Tocci Twins

Despite having their names readily available, more mystery surrounds the subjects of the next cabinet card. Giovanni (L) and Giacomo (R) Battista Tocci were born in Locana, Italy in either July or October in the late 1870s. They were the first two of a total of nine children born to their parents.

The two were conjoined from the sixth rib down, each controlling their respective side. They were unable to walk, but could stand with assistance.

From infancy the brothers were exhibited at freakshows around Europe with their father as their manager. They were seemingly well educated despite growing up entirely in the freakshow circuit and spoke several languages.

Giacomo was talkative and extroverted with a taste for mineral water and sketching, while Giovanni was more introverted and preferred beer. Like many brothers, their differing personalities sometimes led to disagreements ending in fisticuffs.

The pair came to the United States in 1891 at an initial pay of $900 per week, touring for several years there until they ultimately decided to retire to a high-walled villa in Venice in 1897.

Mark Twain was inspired to write the short story Those Extraordinary Twins after seeing a photo of the Tocci brothers during their United States tour.

From there, little is definitely known about the rest of their secluded lives. All we know with certainty (if we trust certain newspaper sources) is that in 1904 the pair may have married two women, with a supposed media scandal following the nuptials owing to their shared body.

There are several differing accounts on the date of the twins’ deaths. Some claim they passed in 1906, though other reports claim they were alive and well in 1911 and 1912. The furthest report states that they died childless in 1940. Their final resting place is unknown.

The Legacy of the Freakshow

The mystification of disabilities began to wane as the 19th century drew to a close. Medical advancements meant more was understood about these ailments, and the rise of disability rights meant these individuals were starting to be viewed with sympathy instead of morbid curiosity.

Another turning point was the release of the Tod Browning film Freaks in 1932. The film—which employed several famous “freaks,” including Schlitzie, Prince Randian, Harry Earles, Johnny Eck, and more—depicts these performers not only working their trade, but also living normal lives behind the scenes along with their “normal” colleagues. They form friendships, romances, hostilities.

The film was heavily censored due to its “shocking” content, with initial screenings resulting in people running out of the theater, viewers fainting, and even one woman threatening to sue MGM claiming the film caused her to miscarry. Despite it being cut down from 90 minutes to just over an hour, the film’s ultimate intention remained. Just as it was claimed on posters for its release:

“What about the Siamese twins—have they no right to love? The pin-heads, the half-man, half-woman, the dwarfs! They have the same passions, joys, sorrows, laughter as normal human beings. Is such a subject untouchable?”

The film was a critical failure panned across the board, still considered shocking after its heavy-handed edits, but some critics still found merit in it. As Richard Watts, Jr. writes for The New York Herald Tribune, “Yet, in some strange way, the picture is not only exciting, but even occasionally touching.”

This growing acceptance was a double-edged sword, as on the whole it was necessary for society to advance to the point of viewing these people as the human beings they had always been.

On the other hand, the banning of freakshows meant that many of these performers—both exploited and otherwise—were out of work, and would find it exceedingly difficult to find other employment in cases of extreme disability or simply due to the fact that performing had been their entire lives. They knew nothing but displaying themselves in this voyeuristic fashion.

It was an extremely lucrative business for many, as we saw with the Tocci brothers, with some performers pulling in up to $500 dollars a week. The loss of any income is devastating, but certainly moreso when it’s that much, with no backup options or government protections. Many performers died destitute and impoverished, forgotten by the crowds that had marveled at them like a child’s plaything discarded in favor of the latest novelty.

While writing this article, I struggled to find an apt conclusion to my work. Naturally I didn’t want to pass off the exploitation of disabled individuals in a wholly positive light, but neither did I want to dismiss the autonomy that this work provided these people in many cases.

How do we collect this information in a way that isn’t furthering the exploitation of the subjects, and isn’t othering to modern viewers with disabilities? What can we do so that simply carrying the pieces in our collections doesn’t feel like a Victorian spectacle brought into the 21st century?

As a historian, it is my job to portray facts objectively. I can condemn the exploitation of hundreds from the comfort of my modern viewpoint, while having to acknowledge that this was a massive part of the culture at the time. I don’t have to like it. History often puts its worst foot forward, and it is our job to find the humanity within.

During my research, I found the article “In the Shadow of the Freakshow: The Impact of Freakshow on the Display and Understanding of Disability Tradition History in Museums” by Richard Sandell et. al. as published in Disability Studies Quarterly in 2005. Their focus was my exact struggle as a museum professional, and what many other museums grapple with. Their conclusion was similar to mine.

Museums have a sacred duty to educate. More than that, though, museums have a duty to help people from all walks of life understand their place in this world, to show them all that they belong and that their stories deserve to be told.

The subjects of this article are not currently on display in our museum, nor are any of the subjects even from Morrison County, but that doesn’t mean work can’t be done behind the scenes to make things right.

At the very least, I can now update our records with more accurate and respectful labeling. While it may have been an acceptable label at the time the piece was accepted into our collections, museums aren’t stuck in the past. They simply take care of the past. I can now give Robert and Ida their names back, no longer just an unidentified couple reduced to their disability.

~Grace Duxbury, Museum Manager

Article originally appeared in Morrison County Historical Society Newsletter, Vol. 37, No. 1

–

SOURCES

The Bangor Daily News (Bangor, ME): “Anna K. Littlefinger Well Known Midget Dies at Vassalboro,” August 23, 1937

Bondeson, Jan. The two-headed boy, and other medical marvels. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004.

The Brownsville Herald (Brownsville, TX): February 28, 1932

The Centre Democrat (Bellefonte, PA): “A Lilliputian Wedding,” March 22, 1883

The City Itemizer (Water Valley, MS): October 25, 1917

“Critics’ Corner: Freaks.” TCM Presents: The Essentials. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://web.archive.org/web/20151230045341/http://www.tcm.com/essentials/article.html?cid=581452&mainArticleId=581107.

FamilySearch. Robert Henry Huzza. https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/LK9R-SBW

“Florida Deaths, 1877-1939”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FP38-6NR : Thu Nov 16 23:39:07 UTC 2023), Entry for Robert Henry Huzza and , 14 Dec 1929.

The Hattiesburg News (Hattiesburg, MS): November 30, 1910

The Human Marvels, “The Tocci Twins – The Blended Brothers,” https://www.thehumanmarvels.com/the-tocci-twins-the-blended-brothers/

The Kennebec Journal (Augusta, ME): “Elect Bert True of Riverside Master of Masonic Lodge,” September 22, 1945

The Little Falls Herald: September 2, 1902

Moberly Monitor-Index and Moberly Evening Democrat (Moberly, MO): February 20, 1932

The News-Press (Fort Myers, FL): “Buster Littlefinger was a Whipsnapper,” October 16, 1969

Ottumwa Semi-Weekly Courier (Ottumwa, IA): “Tiny Woman Dies,” March 14, 1901

The San Francisco Call (San Francisco, CA): February 19, 1899

Sandell, Richard, Annie Delin, Jocelyn Dodd, and Jackie Gay. “In the Shadow of the Freakshow: The Impact of Freakshow Tradition on the Display and Understanding of Disability History in Museums.” Disability Studies Quarterly 25, no. 4 (2005). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v25i4.614.

Smith, Angela (2012). Hideous Progeny: Disability, Eugenics, and Classic Horror Cinema. New York: Columbia University Press.

The St. Paul Daily Globe (St. Paul, MN): “The Smallest Mason,” January 31, 1892

Syracuse University Libraries, Ronald G. Becker Collections of Charles Eisenmann Photographs,Syracuse, New York. https://library.syracuse.edu/digital/guides/b/becker_eisenmann.htm

Hi, I was able to find a bit of information about Buster Littlefinger. The 1940 census has him, as a lodger, in Patterson, New Jersey. No address is given. Bummer. His occupation is listed as Show Business/ Carnival.

Wow, Sharon, thank you for this information on Buster! It’s great when we get a another page in the life story of someone long passed.

Oops. I’m looking at the census. It was actually taken in Vassalboro, Maine. Must have been performing there at the time.

A great article, and well-researched! I looked around in online newspaper archives (which are always being added to) and found a bit more about Buster Littlefinger. In the Minneapolis Morning Tribute of August 21, 1957, there’s a photo of him hammering in a large tent-stake, titled “Midget on Midway” — he was then working for Royal American Shows. In the Edmonton Journal of July 16, 1957, there’s another photo, captioned “Smallest Talker on Fair’s Midway Four-Foot Expert at Drawing Crowds. And then, sadly, in the Lewiston Daily Sun of August 13, 1958, there’s a notice: “Lewiston Police were asked by NY City Police to locate relatives of a Buster Littlefinger, 44, who died in that city” — apparently at one time he’d lived in Lewiston.

Hi Russel, thank you for this information. It is sad to find out but it’s invaluable to understanding life for disabled people in the past.